Working on Your Project

No matter if you created a brand new repository or if you cloned an existing one - you now have a local Git repository on your computer. This means you're ready to start working on your project: use whatever application you want to change, create, delete, move, copy, or rename your files.

Concept

The Status of a File

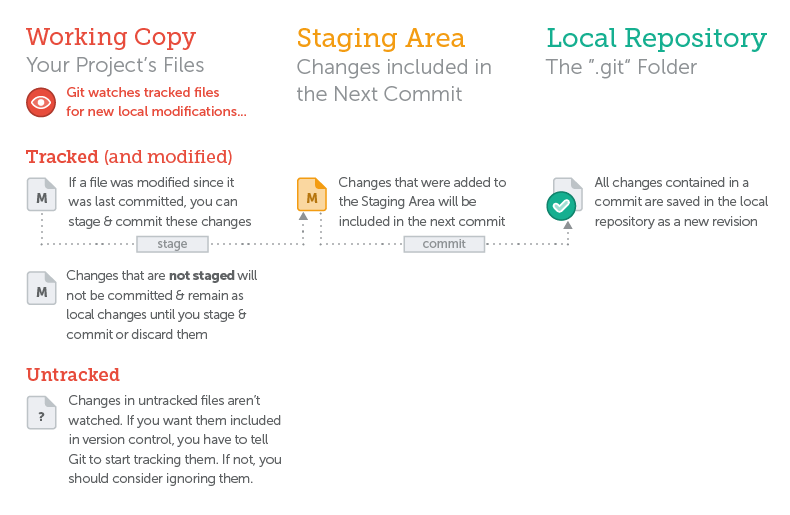

In general, files can have one of two statuses in Git:

- untracked: a file that is not under version control, yet, is called "untracked". This means that the version control system doesn't watch for (or "track") changes to this file. In most cases, these are either files that are newly created or files that are ignored and which you don't want to include in version control at all.

- tracked: all files that are already under version control are called "tracked". Git watches these files for changes and allows you to commit or discard them.

The Staging Area

At some point after working on your files for a while, you'll want to save a new version of your project. Or in other words: you'll want to commit some of the changes you made to your tracked files.

The Golden Rules of Version Control

No. 1: Commit Only Related Changes

When crafting a commit, it's very important to only include changes that belong together. You should never mix up changes from multiple, different topics in a single commit. For example, imagine wrapping both some work for your new login functionality and a fix for bug #122 in the same commit:

- Understanding what all those changes really mean and do gets hard for your teammates (and, after some time, also for yourself). Someone who's trying to understand the progress of that new login functionality will have to untangle it from the bugfix code first.

- Undoing one of the topics gets impossible. Maybe your login functionality introduced a new bug. You can't undo just this one without undoing your work for fix #122, also!

Instead, a commit should only wrap related changes: fixing two different bugs should produce (at the very least) two separate commits; or, when developing a larger feature, every small aspect of it might be worth its own commit.

Small commits that only contain one topic make it easier for other members of your team to understand the changes - and to possibly undo them if something went wrong.

However, when you're working full-steam on your project, you can't always guarantee that you only make changes for one and only one topic. Often, you work on multiple aspects in parallel.

This is where the "Staging Area", one of Git's greatest features, comes in very handy: it allows you to determine which of your local changes shall be committed. Because in Git, simply making some changes doesn't mean they're automatically committed. Instead, every commit is "hand-crafted": each change that you want to include in the next commit has to be marked explicitly ("added to the Staging Area" or, simply put, "staged").

Getting an Overview of Your Changes

Let's have a look at what we've done so far. To get an overview of what you've changed since your last commit, you simply use the "git status" command:

$ git status

# On branch master

# Changes not staged for commit:

# (use "git add/rm <file>... " to update what will be committed)

# (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working

# directory)

#

# modified: css/about.css

# modified: css/general.css

# deleted: error.html

# modified: imprint.html

# modified: index.html

#

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

# new-page.html

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Thankfully, Git provides a rather verbose summary and groups your changes in 3 main categories:

- "Changes not staged for commit"

- "Changes to be committed"

- "Untracked files"

Getting Ready to Commit

Now it's time to craft a commit by staging some changes with the "git add" command:

$ git add new-page.html index.html css/*With this command, we added the new "new-page.html" file, the modifications in "index.html", and all the changes in the "css" folder to the Staging Area. Since we also want to record the removal of "error.html" in the next commit, we have to use the "git rm" command to confirm this:

$ git rm error.htmlLet's use "git status" once more to make sure we've prepared the right stuff:

$ git status

# On branch master

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

#

# modified: css/about.css

# modified: css/general.css

# deleted: error.html

# modified: index.html

# new file: new-page.html

#

# Changes not staged for commit:

# (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

# (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working

# directory)

#

# modified: imprint.html

#

Assuming that the changes in "imprint.html" concerned a different topic than the rest, we've deliberately left them unstaged. That way, they won't be included in our next commit and simply remain as local changes. We can then continue to work on them and maybe commit them later.

Committing Your Work

Having carefully prepared the Staging Area, there's only one thing left before we can actually commit: we need a good commit message.

The Golden Rules of Version Control

No. 2: Write Good Commit Messages

Time spent on crafting a good commit message is time spent well: it will make it easier to understand what happened for your teammates (and after some time also for yourself).

Begin your message with a short summary of your changes (up to 50 characters as a guideline). Separate it from the following body by including a blank line. The body of your message should provide detailed answers to the following questions: What was the motivation for the change? How does it differ from the previous version?

The "git commit" command wraps up your changes:

$ git commit -m "Implement the new login box"If you have a longer commit message, possibly with multiple paragraphs, you can leave out the "-m" parameter and Git will open an editor application for you (which you can also configure via the "core.editor" property).

Concept

What Makes a Good Commit?

The better and more carefully you craft your commits, the more useful will version control be for you. Here are some guidelines about what makes a good commit:

-

Related Changes

As stated before, a commit should only contain changes from a single topic. Don't mix up contents from different topics in the same commit. This will make it harder to understand what happened. -

Completed Work

Never commit something that is half-done. If you need to save your current work temporarily in something like a clipboard, you can use Git's "Stash" feature (which will be discussed later in the book). But don't eternalize it in a commit. -

Tested Work

Related to the point above, you shouldn't commit code that you think is working. Test it well - and before you commit it to the repository. -

Short & Descriptive Messages

A good commit also needs a good message. See the paragraph above on how to "Write Good Commit Messages" for more about this.

Finally, you should make it a habit to commit often. This will automatically help you to keep your commits small and only include related changes.

Inspecting the Commit History

Git saves every commit that is ever made in the course of your project. Especially when collaborating with others, it's important to see recent commits to understand what happened.

Note

Later in this book, in the "Sharing Work via Remote Repositories" chapter, we‘ll talk about how to exchange data with your coworkers.

The "git log" command is used to display the project's commit history:

$ git logIt lists the commits in chronological order, beginning with the newest item. If there are more items than it can display on one page, the command line indicates this by showing a colon (":") at the end of the page. You can then go to the next page with the SPACE key and quit with the "q" key.

commit 2dfe283e6c81ca48d6edc1574b1f2d4d84ae7fa1

Author: Tobias Günther <support@learn-git.com>

Date: Fri Jul 26 10:52:04 2013 +0200

Implement the new login box

commit 2b504bee4083a20e0ef1e037eea0bd913a4d56b6

Author: Tobias Günther <support@learn-git.com>

Date: Fri Jul 26 10:05:48 2013 +0200

Change headlines for about and imprint

commit 0023cdddf42d916bd7e3d0a279c1f36bfc8a051b

Author: Tobias Günther <support@learn-git.com>

Date: Fri Jul 26 10:04:16 2013 +0200

Add simple robots.txt

Every commit item consists (amongst other things) of the following metadata:

- Commit Hash

- Author Name & Email

- Date

- Commit Message

Glossary

The Commit Hash

Every commit has a unique identifier: a 40-character checksum called the "commit hash". While in centralized version control systems like Subversion or CVS, an ascending revision number is used for this, this is simply not possible anymore in a distributed VCS like Git: The reason herefore is that, in Git, multiple people can work in parallel, committing their work offline, without being connected to a shared repository. In this scenario, you can't say anymore whose commit is #5 and whose is #6.

Since in most projects, the first 7 characters of the hash are enough for it to be unique, referring to a commit using a shortened version is very common.

Apart from this metadata, Git also allows you to display the detailed changes that happened in each commit. Use the "-p" flag with the "git log" command to add this kind of information:

$ git log -p

commit 2dfe283e6c81ca48d6edc1574b1f2d4d84ae7fa1

Author: Tobias Günther <support@learn-git.com>

Date: Fri Jul 26 10:52:04 2013 +0200

Implement the new login box

diff --git a/css/about.css b/css/about.css

index e69de29..4b5800f 100644

--- a/css/about.css

+++ b/css/about.css

@@ -0,0 +1,2 @@

+h1 {

+ line-height:30px; }

\ No newline at end of file

di.ff --git a/css/general.css b/css/general.css

index a3b8935..d472b7f 100644

--- a/css/general.css

+++ b/css/general.css

@@ -21,7 +21,8 @@ body {

h1, h2, h3, h4, h5 {

color:#ffd84c;

- font-family: "Trebuchet MS", "Trebuchet"; }

+ font-family: "Trebuchet MS", "Trebuchet";

+ margin-bottom:0px; }

p {

margin-bottom:6px;}

diff --git a/error.html b/error.html

deleted file mode 100644

index 78alc33..0000000

--- a/error.html

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,43 +0,0 @@

- <html>

-

- <head>

- <title>Tower :: Imprint</title>

- <link rel="shortcut icon" href="img/favicon.ico" />

- <link type="text/css" href="css/general.css" />

- </head>

-

Later in this book, we'll learn how to interpret this kind of output in the chapter "Inspecting Changes in Detail with Diffs".

Time to Celebrate

Congratulations! You've just taken the first step in mastering version control with Git! Pat yourself on the back and grab a beer before moving on.

Get our popular Git Cheat Sheet for free!

You'll find the most important commands on the front and helpful best practice tips on the back. Over 100,000 developers have downloaded it to make Git a little bit easier.

About Us

As the makers of Tower, the best Git client for Mac and Windows, we help over 100,000 users in companies like Apple, Google, Amazon, Twitter, and Ebay get the most out of Git.

Just like with Tower, our mission with this platform is to help people become better professionals.

That's why we provide our guides, videos, and cheat sheets (about version control with Git and lots of other topics) for free.